Obituary for Ira J. Winn

February 1929 — December 2020

by Ian Muir Winn

Ira J. Winn was a kind, gentle, and thoughtful man, thin but fit, with an easy laugh and a penchant for terrible puns. He was a professor — emeritus he'd be the first to tell you — of education, urban planning and environmental studies, beloved by many of his former students and remembered for his signature technique of using case studies to inspire critical thinking, rather than relying on textbooks. He is survived by Arlene, his wife of 54 years and me, his only child.

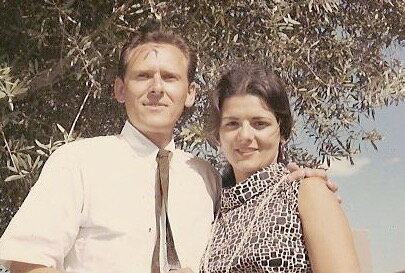

My father was born in Boston, went to college at the University of Illinois and took a train out west to escape the cold. He settled in Los Angeles where he bought his first car, a 1950 Chrysler Imperial. He purposely never fixed the passenger door — which was held closed by a piece of rope — to test the girls he dated for being “snooty”. Ever since he was first issued a passport he was an avid international traveller. From Malawi on a Fulbright scholarship, to Israel, where we lived for half a year, to Costa Rica, China, Russia, Brazil… Indeed, my mother fell in love with him while he was leading a tour group through Europe, something he did annually. They had met ten years before when he was the dishy teacher of her high school civics class at Hamilton High but he didn’t remember her — and reportedly only gave her a B! My mother’s father was less than pleased with their relationship. He wanted his daughter to marry a real doctor, not some jumped-up doctor of education. When my grandfather offered to settle the dispute with boxing gloves, my parents eloped to Las Vegas — or Clark County as he was quick to correct me. Pops hated Vegas and instilled that hatred in me. A vulgar, artificial place. A waste of water. I can see him smiling now.

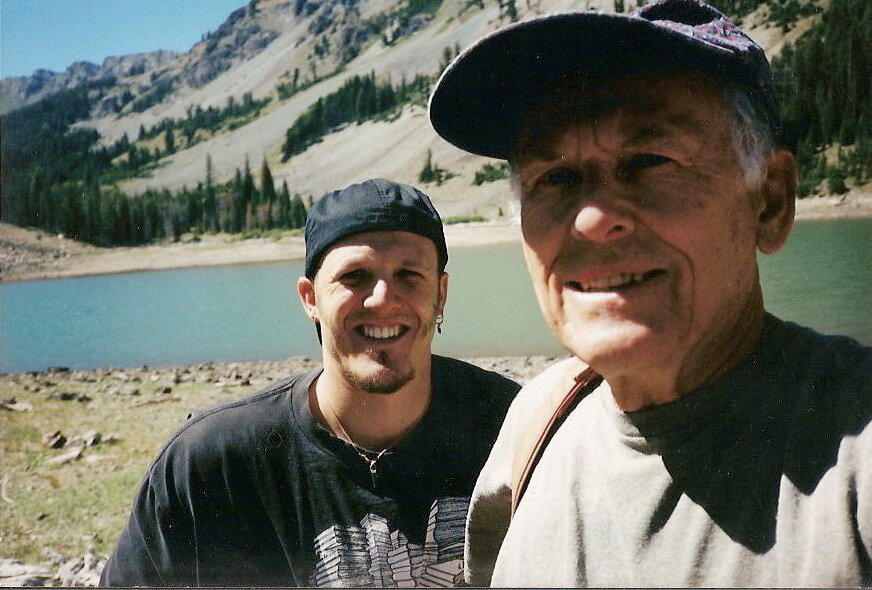

After receiving his doctorate at UCLA, he was selected by USAID to help develop educational opportunities in Brazil, where I was conceived. After three years in Rio de Janeiro he went on to teach at Cal State Northridge for thirty-eight years. As I proudly told my school friends, he taught teachers to teach teachers to teach. Back in those days, my father loved to spend time in wilderness, especially Yosemite National Park. In fact, he named me after one of the park’s progenitors: John Muir, renowned naturalist and founder of the Sierra Club. While I was growing up, my father would often take me hiking in the mountains and deserts surrounding LA. Family trips were to national parks and monuments in California, Arizona, New Mexico and Washington, where he and my mother have, and had, many friends. My father remains the worst fisherman I have ever met. We would go to bait and tackle shops, consult successful anglers and mimic their reels but I didn’t catch a single fish until the day he threw down his rod and walked away in disgust. Within ten minutes I had a trout, much to his chagrin. My father loved to give advice. The best he gave to me was when I was negotiating a publishing deal and he said down the phone to me in London, “Don’t fall on your sword.” The novel resulting from that deal introduced me to Cat, my wife of fifteen years and a woman my father would come to call his daughter. Estranged from her own family, Cat found, in Ira, the only loving father she has ever known. The day she and I got married on a beach in Cayucos was the happiest I’ve ever seen him. He said, “Happiness is when your son gets married and your dog dies.” He never did like that dog. One time at the dinner table he even pointed at her and said, “That dog is aloof and doesn’t respond well to affection.” The table burst out laughing. I said, “Who we talking about here, Pops?”

My father was a keen gardener and the vases we have arranged for him around his shrine here in London (where I have decided to remain out of respect for the vulnerable — though I will host a zoom memorial) hold the Asian lilies he gave us several years ago. They have since taken over part of our garden and are miraculously still in bloom in late December. Growing up, I remember my father taking me on night raids to various building sites to covertly shovel soil into burlap bags. Yes, friends, my father was a dirt burglar. When asked about his garden, he would always say he liked to watch things grow.

My father and I loved each other, even if we didn’t understand the other’s choices. He thought I should have continued my education, and/or gotten a “job”. I thought if he were going to teach and preach environmentalism he should at least try to reduce his carbon footprint, especially as regards to cruises, which he became fond of in his later decades. My father retired to San Luis Obispo and though he very much enjoyed working as a mediator for the courts, having coffee with his men’s group, and writing political articles for the local papers, retirement did not suit him, nor did the digital age. He became restless, irritable, curmudgeonly. He was famous for strapping his giant desktop to the passenger seat and driving to the Apple store for help in accessing his email — talk about your portable computer! He never, to my knowledge, used an ATM and the digitalization of information bewildered and annoyed him, as he often let me know.

“Those idiots at Apple don’t know how to make things simple. How am I supposed to know what the command key is?”

“Um, those idiots at Apple have built the most powerful communication devices in human history.”

“I know! Idiots!”

But my father was of the Greatest Generation. He was born in the year of the Great Depression. He lived through World War II, the polio pandemic, the Korean War (which injuries from a traffic accident kept him out of), the Vietnam era, the civil rights movement, “that schmuck” Richard Nixon, sixteen years under his despised Ronald Reagan (both as governor of California and as president), 9/11, the Iraq Wars, the 2008 financial crises and the catastrophic early effects of climate change. But not 2020. And not Covid-19.

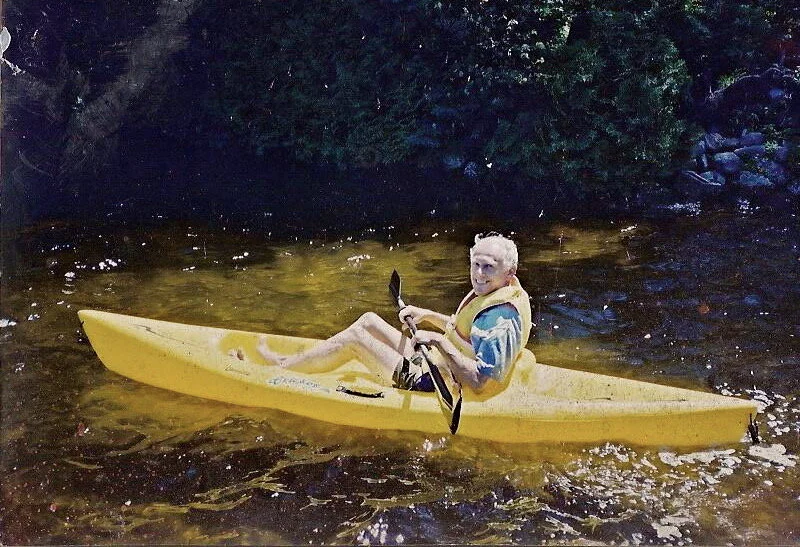

My father tested positive for coronavirus in early December. Two weeks later, too weak to walk, he died with an oxygen tube under his nose and powerful opiates in his bloodstream. He died peacefully by all accounts, at his excellent care home, Bob and Corky’s #5. I am very grateful for the level of care he received there in his final months and days, and to my mother for placing him there after he suffered a neurological event in 2019. His last bite was apparently peach yogurt mixed with finely diced watermelon, which is not a bad bite all things considered. For the last eighteen months of his life, Cat and I called him every day and spoke to him through headphones. We can chart his decline by the average daily minutes to him on our phone bill: from thirty on admission, to twelve this past summer, to his final week where we simply talked to him soothingly, often without response — though I did elicit some laughs from him a few days before he died so clearly his evolved sense of humor survived until the end. Dressed in full PPE, my mother was able to visit him and hold his hand in his last days, surely an incredible comfort. The hospice nurse said he smiled when last we called. Down the phone, Cat and I sent him love. We told him it's okay, that we’re proud of him, that he will be remembered, that we love him and that, if he wants to go, not to be afraid. To just float on down the river. That our love for him will endure throughout the journey and beyond. I told him one day I’d meet him in the ocean, whatever that might mean to him. I told him I believe that love endures beyond the grave. Cat said Buddhist prayers.

He will be missed.

If you’d like to make a donation in his name, please do so at: https://ecoslo.org/donate/. It’s for the trees!

His zoom memorial can be found here. Many thanks to all who attended!

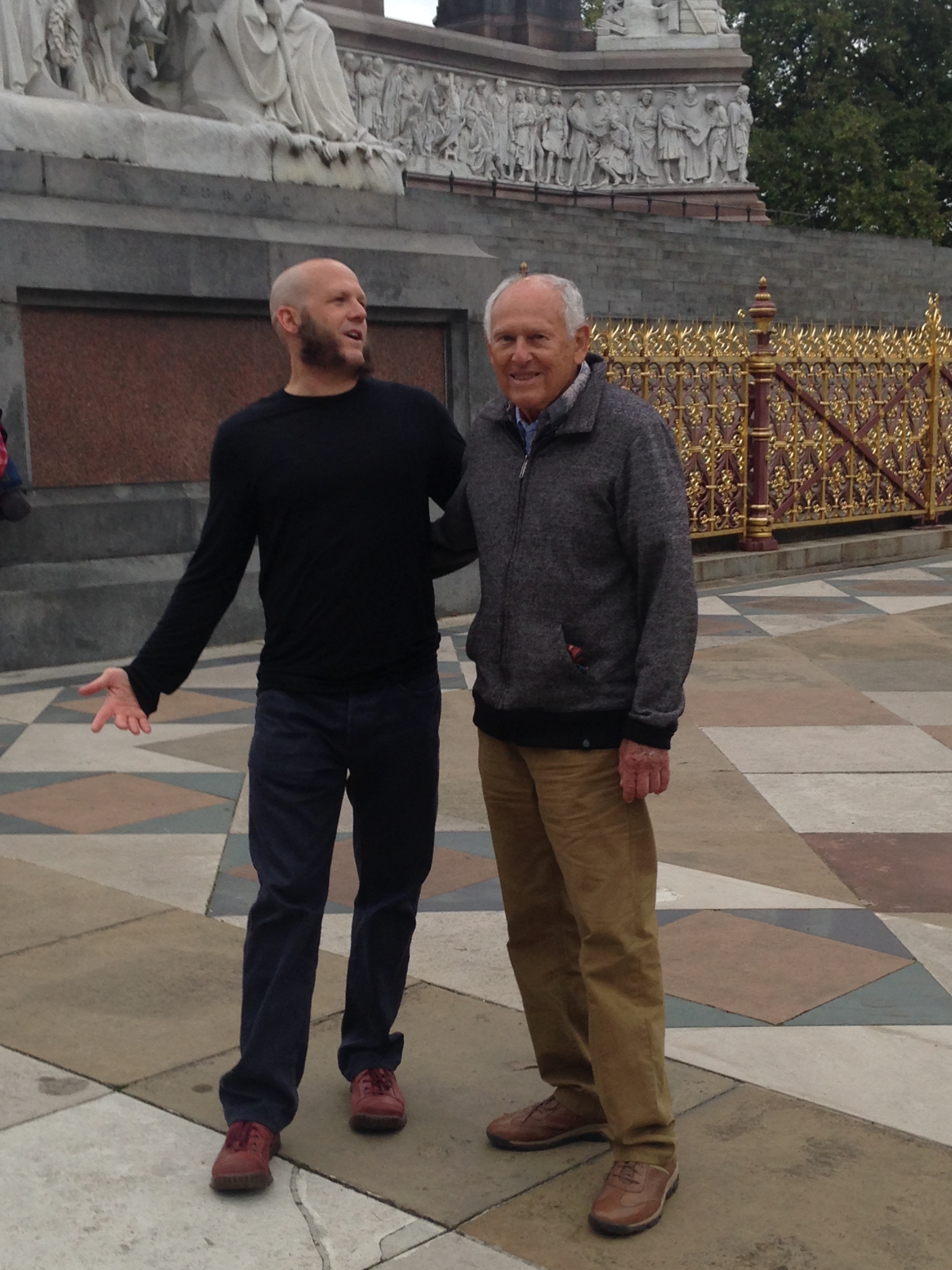

Lastly, please enjoy this gallery of the last time Pops came to visit us in London!